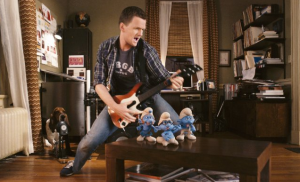

Hollywood will be smurfing our theaters with the new Smurfs movie, released on August 3, 2011:

I’m no longer the type of person to decry the end of Hollywood’s creativity or bitch about the onslaught of lazy slop of reboots, remakes, sequels, prequels, “re-visionings,” and poor adaptations. I’ve heard all the complaints, whines, eye-rolling comments, and exasperations. Don’t get me wrong, I agree. But there’s no point complaining, since Hollywood and the rich executives who run them will continue to produce them. Marmaduke. Underdog. Yogi Bear. Alvin and the Chipmunks. They’re just gonna keep coming.

And why not? People go and see them. And the public isn’t exactly running to the original stuff – Inception being the exception (and even that has its problematic justifications). Besides, beyond the lame premises, people do work on these films, and arguably a few of them actually work hard on their respective roles. And, I’ll be honest: on a slow day in the future, when it’s on TNT and I’m bored and have time to kill, I may watch an hour of one of these films. Hell, I saw twenty minutes of Underdog while at the gym. Stupid, but hearing Patrick Warbuton say “Dogfish” while wearing a too-tight stocking cap was damn hilarious. (Does the context even matter?)

This write-up isn’t about the hack-work of the Hollywood system (it’s always been there, from the lesser studio system works of the 50s, to the trash-exploitation films of the 70s, to the early TV-show-turned-films of the 90s). This is actually about an interesting set of comments concerning these types of stories and attempts to wrap one’s head around the premises in question. People seem more willing to explore the fringes of a concept a lot more than usual; in other words, they seem to want more “world building”.

In effect, people wants to see characters inhabit their own existence, and the logic in which that existence came to be. Why couldn’t the Smurfs exist in their own world? Why make them interact with humans? The same could be said with Hop. Couldn’t he just be a Easter bunny in an… I don’t know, an Easter bunny world? Or, take Cars – a film which has been sarcastically befuddling people: who built these cars? Why are there sidewalks? And so on.

It’s difficult for me to acknowledge this, but these films are the now-equivalent of the 2D-live action films like Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Space Jam. Unlike today’s CGI/live action films, however, Roger Rabbit and Space Jam at least tried to contextualize their worlds. In Roger Rabbit, cartoon characters were “actors” of their own right in 1940s America; in Space Jam, the animated world, underneath our own, was about to be invaded by aliens. It doesn’t make “full” sense in closer inspection (do animators exist in Roger Rabbit? why would aliens really need to play basketball to global domination?), but there’s enough content to keep our focus and suspend our disbelief.

The problem isn’t really the writers, but the base material and the intended audience. Yogi Bear and the damn-near full gamut of Hanna-Barbara cartoons place animated characters among humans. Looney Toon shorts did too, so it isn’t Cartoon Network’s fault per se that the upcoming cartoon randomly places Bugs and Daffy among a world of humans. They ought to take lessons from Lauren Faust, whose reboot of MLP seem to establish a fully-fleshed world in which the characters can thrive, without falling into the two traps of over-explaining or under-explaining their worlds.

Over-explaining puts -too- much detail into the world, focusing on the excessive details without providing a solid story to work with. Heroes fell into this trap, Final Fantasy games and most JRPGs are notorious for this, and Sonic the Hedgehog fans seem enamored with the details of everything Mobius instead of the story of the comic run (comics, with their constant need for retconning, seems to be the biggest culprit in over-explaining). By contrast, under-explaining creates a broad world without fleshed out rules that fail to stay consistent with the various stories being told. Heroes did this (yes, somehow a show both OVER and UNDER explained its world), and recent shows like V apparently has been throwing a ton of ideas to the wall without anything in place.

Bottom-line: good world building is hard. It takes planning, a dedication to understanding the types of stories you wish to tell, and the surroundings in which you wish to tell it. The characters must be beholden to this world you create, and the audience should be drawn into it. Showcase this world, and let the characters thrive in it, and let the audience figure out where the limits of this world go. Sure, some forms of entertainment can be looser in this regard (take Spongebob, where fires burn and electricity flows freely underwater), but the basis is there (all the characters are underwater species, and mammals need aquatic suites to breath.)

So, really, it’s not a BIG surprise that films like the Smurfs, Hop, and Yogi Bear tosses its characters in the real world and let them do whatever. Why bother to put much thought into the world of such films if their mostly for kids, kids who care very little about “where the sidewalks in Cars” came from? Good world building is better for long-term venues, like television, books, and video games anyway; films, as great as they can be, are difficult to justify in several months of rules, laws, social hierarchies, status quos, and so on. Not to say they can’t exist in cinema, it’s just harder to make it work in three hours or less without over or under-explaining everything.

Towing the line between “but how?” and “who cares?” is a tricky one, especially pushing into sci-fi territory. In a certain way, not only does one have to create a certain level of plausibility in the self-created world, but – and here’s the key – work to deny further inquiry. The limits are not only what the characters can do, but what the audience is willing to believe. Yogi Bear is a good example. He’s a talking, walking bear, so why aren’t they other walking, talking animals? If there were at least 2 or 3 other talking animals, then the audience wouldn’t be so hard-pressed in wondering about Yogi. (In effect, the later Hanna-Barbara crossover films, which contained a number of the talking animal characters, was an easier pill to swallow).

Films are better served to KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) in their worlds unless we’re entering trilogy territory; even then, there’s shaky ground. Both the Matrix and Star Wars were straining by the third film, the former more so than the latter, and the less said about the Star Wars prequels, the better. Books, games, and TV have more time to share their environments in detail, but even they can be over and/or under achieving.

My advice in the art of world building is to let your characters and story define the world, and not the other way around. The goals should reveal the strengths and limits of the environment, no more, no less. Build your conflict, understand your tone and genre, and from there, the rules should automatically come. Don’t force your beliefs, ideologies, or philosophies into the world until and unless they are emphatic to the development of the story or character. And above all, know when to stop. Let the fans fill in the details.

I’m sure all five Smurf fans in existence have already nailed the lore down, so they should be the only ones truly angry come August first.

Comments are closed