Final Space ended its run after three seasons, and honestly, it was to be expected. The ratings for the third season were down rather significantly. While the marketing didn’t really do the show any favors, it was particularly telling how no one across social media seemed to even praise the animation of the show (which continues to be incredible), let alone the show overall. It’s on Netflix now, and there’s a chance that new viewers will latch on the show via binging, arguably a better way to watch the show than week-to-week, and garner so many hits that some kind of finale–weather a season or a movie–could be commissioned. I have my doubts though.

Final Space has been both amazing and frustrating to watch, a rare expansive (and expensive) show of incredible visuals and moments of epic dramatic scale, that nevertheless just could not focus. Final Space feels like the ur-example of the importance of how simply “pacing” can make or break a show. Because Final Space had it all: compelling characters (with perhaps the exception of the lead, but more on this in a second), an escalating set of stakes; a juicy, constantly evolving plot; raw, shifty villains; eye-popping animation, rich themes; and, uh, humor. That last point, as you can see, I hesitated on, because comedy, beyond all that has been mentioned, is wholly dependent on timing and pacing, and because Final Space struggled at pacing overall, a majority of the jokes and humorous moments fell flat.

It’s hard to describe without watching Final Space and seeing the attempts at jokes in action. Generally speaking, the humor was split between “characters with funny voices talk in funny ways” and that kinda of improv-y, stammering humor that seems to be all the rage now. It could be funny, if only because it was inevitable that a certain line reading or a particular reaction would garner laughs, but it was difficult to describe the show as comedic. The scale of Final Space’s dramatic beats were so high that it often became impossible to pull back to make a jokey bit work, and no amount of exasperated reactions and belabored metaphors could really make Gary comedically sharp enough to carry the show the way its creators probably expected. Gary’s most memorable moment across Final Space’s three season had nothing to do with “cookies,” but the brutal, emotional fight between him and Avocato over the truth about Lil’ Cato’s parentage.

In fact, the bits about the cookies are a good example of Final Space’s comedic struggles. Many early jokes wrap around Gary trying to acquire a cookie that’s always out of reach, with increasingly nonsensical obstacles getting in his way, but what isn’t clear is if Gary even likes cookies, or if he just wants one. “Cookie” is a funny sounding word, too, with it’s hard ‘K’ sounds and humorous tints when spoken fast and kind of high-pitched. But it wholly separated from Gary as a character and certainly separated from the intensity of the show, and its clear why this specific joke gets a nigh mention in its third season.

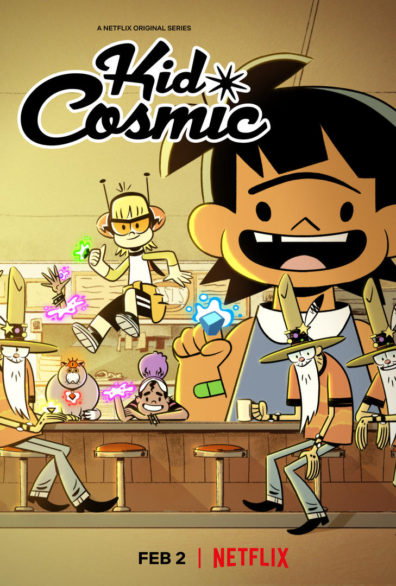

It’s somewhat interesting to compare this show to Kid Cosmic, Craig McCracken’s cracking Netflix series, also about a group of ragtag “nobodies” facing increasingly dire, astronomical dangers. Both shows are clearly aiming for different audiences, but both shows also struggle with squaring its world-ending stakes with its snappy, funnier moments. McCracken, to be clear, is much better at it than Olan Rogers, but I do think the second season goes so far, again, into viciously high stakes that comedic moments feel forced, or leave its characters acting dumber than usual. There is no logical reason whatsoever for Jo to force her team to celebrate at a party filled with bad dudes, after just barely completing a nearly-blown heist from that same party. Jo struggles with tempering her expectations and behaviors as she learns how to be a leader, and forcing “co-workers” to celebrate has the thematic groaner energy that feels familiar and relatable, but to do so at the party you just infiltrated (and almost botched) is an Archer bit of idiocy; sure, it works for that show, but it comes across too dumb here. (I think this episode is meant to arouse suspicion with Queen Xhan, as she is familiar the leader of the villains here, and she’s the one who convinces Jo to celebrate among the criminals they just fleeced, but not only she not a traitor, that red herring leads nowhere else.)

And then there’s the stories of each of these shows, the narrative concocted in order for these shows to reach these dramatic highs. Sci-fi space, with its infinite, unimaginable vastness and the made-up jargon and tech that allows for more made-up adventures and travel within it, requires a deft, comfortable hand in maintaining a clear narrative to follow, to understand what the characters are doing, and why. (The final season of Voltron absolutely gets lost in the weeds with its own lore, becoming a robot-smash, shout-fest of nonsensical terms). The characters in Final Space actually reach Final Space, and I still don’t know what “Final Space” is. Earth is also destroyed twice? I mean, I don’t really need to know the details; I know full well I can do a deep dive into the wikis, or a re-watch, and “figure it out”. It’s really more a matter of character needs and goals, and the specificity of what’s needed, and what obstacles are in their way, and why. That gets muddled pretty fast, and perhaps ten episodes weren’t enough to slow things down to Explain Things and What It All Means, and plopping some riffs with poor comedy here and there made things worse, not (in terms of escapist reprieves) better.

Interestingly enough, Kid Cosmic had the opposite issue, where not even eight episodes, one of which didn’t even crack the fifteen minute mark, possessed enough “stuff” to fill them all. (Which is weird, because you’d think the search for thirteen Rings of Power would have sorts of narrative potential.) There’s a bit of a slag in the middle of the run, which includes a baffling flashback opener of ring acquisitions and losses. Often, character decisions feel more like they’re made for thematic purposes over narrative ones (Jo joining a battle royale just to “prove herself” comes across as silly, regardless of how depressed and down she’s feeling). The escalation what it means to be a hero, and the choices that heroes have to make, is rich thematic fodder but gets muddled when they become prime motivations instead of the specific choices that are needed to solve current narrative problems. (This is kind of a long way around to say it probably would have made more sense for Jo to join that battle royale alone if she noticed the ring of power in Krosh’s eye from the TV commercial; as it stands, Jo yelling “character notes” about proving herself in the midst of battle is kind of sloppy, even in a “kid’s” show.)

And to be clear, both Final Space and Kid Cosmic are filled with rich, powerful moments that, in isolation, are worth it. But these moments often dramatic trees, scattered about a semi-empty field of narrative, crooked branches and comedic weeds. (Gary’s forced, belabored metaphors are rubbing off on me.) Part of me thinks that the rushed schedules of animation is starting to really filter down into the production of these shows, providing less time to really work through the ins and outs of certain plot points or the overall story. Regardless though, both shows never quite could sink its teeth into the universe that it established. I like what I see, but I can never love it.

Still working through how best I want to handle blog posts, I think I’m going to update every two weeks now (which gives me time to work on other projects), and I’m not going to provide summaries or outlines on what I’m gonna write next, because really, it’s all based on what mood strikes me and what I happened to have watched or what I happen to think about at the moment!

Comments are closed