(I’m still trying to figure out how to make titles work for these pieces.)

So I have a question about The Owl House. Was there an episode that, straight up, explained what the main nine witch covens actually are? I did some down-and-dirty research, and a wiki pointed out that the nine were mentioned in an episode call “Covention”. I re-watched “Covention”. They did not mention all nine covens. They mentioned one of the nine covens was “Construction,” which is structured around gaining magical strength, which is also an important plot point of the episode, but I don’t think the gaining of magical stretch is ever brought up again in the entire show. Which is weird, especially towards the end of season one where the magical fights escalate in stakes; no one bothers to use power-gaining to escalate in strength.

When The Owl House was first announced, I was quite looking forward to watching it. It had a really cool, nutty locale and the characters seemed fun and appealing. And don’t get me wrong, The Owl House is quite a fun show, but it also feels… well, perhaps not troubled, but restrained? Unsure of itself? There’s a pretty controversial piece of news about the show (which is subject to change I suppose): after this current second season, The Owl House will have one final third season, consisting of three episodes at about an hour and a half each. Even if you think Disney hates the show (which I don’t think they do, and in the next paragraph I’ll elaborate), this kind of decision is weird and unprecedented. It has the flavors of Netflix’s recent push to end some of its animated shows with movies instead of final seasons (Trollhunters, Hilda), but you can chalk that up to Netflix’s push for more affordable, quick content for weekly, new releases than whole-ass seasons. (They sort of did this with Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and not for nothing, but Arlo The Alligator Boy, a fine movie as is, probably would have worked better across ten episodes.)

I think there’s a lot going on with Disney, partially in relation to Disney+. I suspect, spitballing here, that the mandate to find “the next Gravity Falls” got usurped by the push for Disney+ content, and the pandemic sort of solidified that “Disney+ at all costs” notion. A lot of Twitter seem to think its due to a same-sex dating subplot (and I can’t dismiss that out of hand, as many shows have gotten royally screwed when same-sex narratives pop up), but my inclination is that the ratings, business realities, and poor timing left The Owl House on the chopping block. (I have a theory. If the most social media appeal of your show is a “ship,” your show actually on pretty shaky ground.)

The reason I asked about the nine covens at the beginning of this piece is because I feel like knowing what the nine covens are, and who leads them, and how, specifically, they work within the society of the Boiling Isles, would be pretty important to Luz, and The Owl House as a whole. I get that the show is structured from Luz’s point of view, but as an aspiring witch, knowing what those covens are should be a day one question from her (and I get that she’s not supposed to be a great student but still). This ought to be a pretty clear point that show reveals, to flavor the world better, but to also provide the audience some kind of through-line of the world itself. In “Eda’s Requiem,” we finally see the Bard Coven in action, way late in season two. That seems really late, too me.

(I’ve written before about Anne’s weird season one lack of desire to understand the world of Amphibia, and I feel like Luz and The Owl House come from the same place: an incomplete, unfinished understanding of the world each show has created. Same for Star Vs. The Forces of Evil. Something about the way these shows deal with magic is wild if you think about it. It’s simultaneously overly complex and weirdly simple. What makes those nine covens the main ones versus the others? When Star decided to “end all magic,” why was there so little pushback? I wrote about how strange it is that a telethapy-esque spell took several episodes to set up in The Dragon Prince. Magic used to be portrayed in clear, simple terms (point fingers or wands, say some nonsense, strain oneself a bit, flashing lights!). Sometimes you had to find objects or talismans or horcruxes or runes or “places imbued with special powers”. There’s so much going on with magic in these shows now that it’s bordering on distracting; I feel more and more like I have to understand the depth of these spells to understand the depth of these characters nowadays. I partially have the same feeling for Centaurworld, which I will tackle next week.)

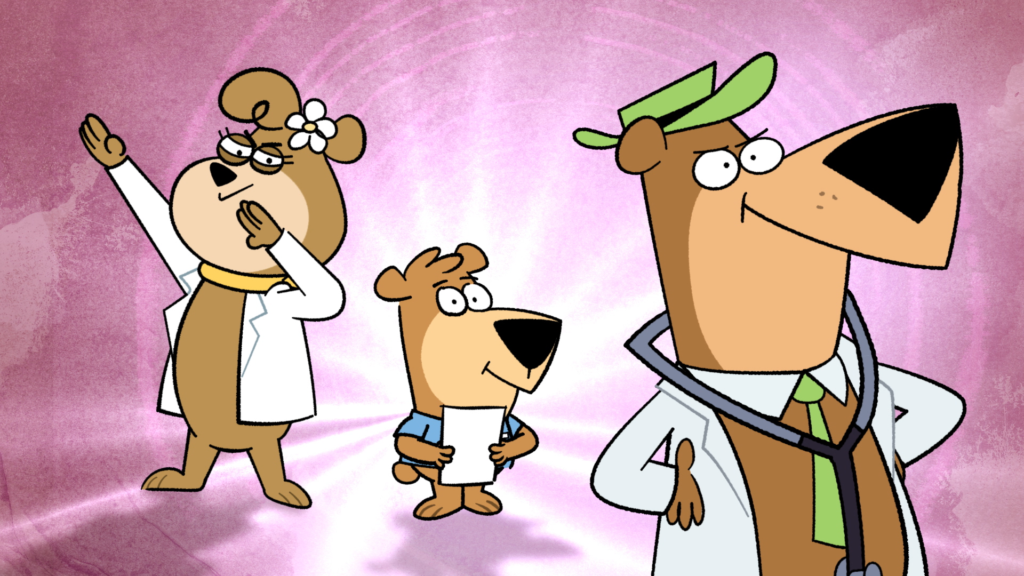

Jellystone, otherwise, is fantastic, and it helps that C. H. Greenblatt is an extremely talented creator, and that the back roster of the sillier Hanna-Barbera cartoons are sketched so thinly that all the new, updated creative choices for these characters work so well. I had my doubts that making Yogi, Cindy, and Boo-Boo doctors/nurses was a good idea, but the core nature of these characters never changed: Yogi is still darkly gluttonous, Boo-Boo is reluctantly submissive, and Cindy… well, Cindy was more the straight-bear of reason; here, she can go toe-to-toe with Yogi on the absurd escalation scale. Greenblatt needed to situation these characters in occupations or locales to give them a broad purpose; the medical field is probably the simplest to utilize, since policing is persona non grata right now, and being a lawyer is probably to complicated to work with in a kids’ show (also its connection to policing).

Many people tend to say Jellystone has a lot of Chowder-type humor, Greenblatt’s first show, but I don’t think that’s true. The two shows have aesthetic similarities for sure, but Chowder was a bit more surreal, I think, and as much as I love that show, you can kind of tell by late in its run it was losing a bit of steam. The world of Chowder was well-drawn but rather limited: you can only do so much with a not-bright, gluttonous kid and his self-absorbed mentor, with an assortment of other weirdo characters to pad things out. Jellystone has a much richer world and character-base to pull from–Hanna-Barbara’s library is rich and varied, and Jellystone has only light touched what it can do with it. Greenblatt and his creative team can make some serious comic moves here (I already thought of two whole potential specs).

More well-known characters like Wally Gator and Snagglepuss, while present, are mere side characters to Jellystone’s heavy hitters like Shag, Augie/Daddy Doggy, and Captain Caveman, who you’d think would have been placed along side the more human characters (more or less used as random shopkeepers and store employees). Loopy gets some choice lines, and I don’t even remember her (well, his) older cartoons ever airing! Top Cat and his crew make splashes, and even the Banana Splits pop up as heavy hitters. Jellystone knows that it has some freedom to re-tool a batch of characters that didn’t exactly hold up well (in the fact that probably seventy percent of these Hanna-Barbera characters have been forgotten by most people). So just the idea that we could see some deep cut characters pop up and steal the show already provides Greenblatt with swaths of material that he lacked in both Chowder and Harvey Beaks.

I’ll probably dabble with the end of The Bad Batch next week, along with a few words about Centaurworld, because I have some stuff to say about that show.

Comments are closed