My name is Kevin Johnson. I am a gamer. I am a feminist.

I have issues with gamers. I have issues with feminists.

I. A Case Study

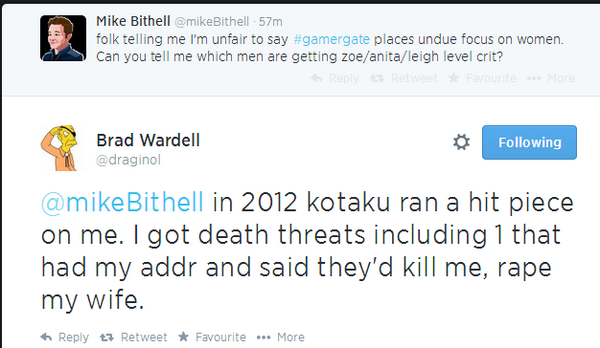

Among the many, many things being tweeted and written about concerning #Gamergate, this was among them:

Curious, I took a look at the so-called hit piece.

I’m not sure if the definition of “hit piece” changed over the years, but what I see is a pretty cut-and-drive piece of investigative journalism, exploring the fallout of a disastrous game release. It involves a lawsuit between Alexandra Miseta and Brad Wardell, of claims and counter-claims, of dismissals and motions to block them. It doesn’t make any side look too pretty, and most likely this information was discovered when Kotaku sought to investigate why this game failed so miserably. This is on par with investigations, really. Watergate, which Gamergate derived its name from (and so, so many other misguided large-scale scandals), began with two reporters looking into a really odd break-in.

If Brad’s response is true – and, for the full purposes of this piece, I will assume all accusations of rape and death as true – then already we see the trouble. It’s absolutely horrific, but characters of ill-repute and good-repute has gotten threats as well – Bernie Madoff, George Bush, Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton. All of these threats are indeed awful and should be treated with the utmost seriousness, but I noticed that Wardell’s wife received the rape threat, who, for all intents and purposes, is completely innocent of the lawsuit. Oddly enough, in this overall discussion about how much misogyny has to do with this scandal, many supporters of Gamergate circulate this tweet to support their cause. But right there, with the rape threat of a woman not involved in any way with this situation, pushes back against that argument. In addition, its probably safe to assume a “gamer” was the one who made that threat, by which I mean that a person who is familiar with Kotaku and the piece, and therefore has some intimate relationship with games. He is probably male, based on the idea that a woman threatening to rape another woman is rarer still, but I do not discount the possibility. In either case, a threat was made against someone, a female someone, far removed from the lawsuit, and by every journalistic definition, that Kotaku piece is far from a hit piece.

I’m also aware of Mike Bithell’s initial tweet. It’s not necessarily too hard to look for various places where death threats have been lobbied towards male writers, particularly when they review socially popular games and deem them less than perfect. And as Gamergate takes speed, there is a tendency for its proponents to focus solely on the initial harassment and not look, at least partially, in some of the more pressing issues that Gamergate supporters are concerned about – the overall improvement of game journalism (the core of which, to be clear, may be different than what most Gamergate supporters are actually advocating for).

This entire Gamergate situation, from the outside looking in, is vile and nonsensical, a “much ado about nothing” wave of gibberish among stereotypical gamers. Inside, however is a powerful stalemate of massive cultural forces, of gamers pushing against their stereotypes as typical male angry youths; fortunate game journalists’ defensiveness against a growing populous voice desperate to be heard; feminist forces demanding equal and improved treatment against a contingent of males (and females) who believe that such a thing is, and should be, no big deal. The civil voices trying to make some sense of it all are drowned in violent, sexist threats and the mass shunning of a culture who will not be shunned. And in the midst of it all, it’s gaming and gaming reporting which suffers.

II. The origins and fallout of Gamergate

At this point it’s pretty much agreed what prompted Gamergate, but the overall response to that prompt is massively distorted. Zoe Quinn created a game called Depression Quest, which got generally good reviews from most gaming sites. However, it was revealed that she was dating a writer from Kotaku (information divulged from a ex-boyfriend), which prompted some concern from many readers of the site about biased reported. The Kotaku senior editor swore that no ethical injustice has occurred (and the writer was not the one who wrote the review on Depression Quest), but the flood gates had parted. I should also mention that there’s a sense among gamers that Depression Quest is actually not that good (or perhaps worthy) of a game, which runs counter to the reviewers’ high praises, and that seems to have caused its own bit of consternation.

Not quite related, but significant nonetheless, has been the most recent release of Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency program, which discusses various sexist tropes in video games. I don’t one hundred percent agree with Sarkeesian’s points, but sexism in gaming, like most entertainment sources, comes from laziness more so than misogyny; the question she, and many others, are asking is why, when given the lazy choice, do we resort to utilizing women in half-handed fashion.

The combination of these two events created an flaming uproar, the fires of which was stoked by things like the JonTron vs. Tim Schafer argument on Twitter, and reports that both Sarkeesian and Quinn had to flee their homes and report to the police after some of the rape and death threats grown too close to home. A curious thing happened; after Sarkeesian made her report, she asked for a donation to her show. This seemed to be the defining moment that Gamergate went from a typical gamer rant against encroaching censorship into all-out war against game writers. The conflictual threat of fearing for your life followed by the request for money had many, many people calling foul. Now the argument was about game writers, critics, and journalists using their experiences and connections to make extra, easy, and manipulative money off corporate kickbacks and the hard work of gamers. There’s definitely an air of sexism here, but there’s a hint of social unrest, too – game journalists, who’s credentials as writers (let alone journalists) are questionable, sitting in their rooms or offices and playing games for free and writing opinions as law while gamers are shelling out $40-$600 or more bucks on games, software, hardware, and DLC to have their voices unheard. Sure, most game journalists aren’t paid that well, but they DO receive kickbacks, even if it’s in the form of free games and invites to events, and most gamers aren’t exactly financially well off. Nothing says this more than E3 coverage, which tends to have more people writing about HOW MUCH WORK THEY HAVE instead of actually working.

Like it or not, Gamergate is a thing. It’s lots of things, really, but it’s a lot of accusations and misunderstandings, not only of what feminism is, but what journalism is, what writing is, what “game culture” is, and what “game culture” means to millions and millions of fans. Times are changing, and how we discuss games is changing, but there are those on both sides of the aisle who refuse to budge; the gamers sick of the discussions of sexism, the writers tired of being lumped into the “gamer” stereotype, the gamers tired of being lumped into the “gamer” stereotypes, and everyone else trying to get in a word edgewise about minority/LBTQ representation, about labor issues and improving the overall game and game market, and about finding information on the next big game coming out. It’s that unwillingness to budge, that inability to acknowledge that there are serious problems with gamers, game journalism, and feminism, that caused Gamergate to reach this point.

III. The problem with gamers

I am a gamer. I make no qualms or parameters on what “real” gaming is or what a “real” gamer plays. Gamers play games, no matter how hardcore or casual. I might say that gamers, at least somewhat, should be interested in broad gaming events or releases, but that’s hardly a qualifier. Gaming enthusiasts or gaming fans, on the other hand, I think should be interested in, if not the variable genres of games available, at least in the way we talk about and discuss games to improve them and their cultural cache. The question is how to do that, specifically, but the discussion is a good start. There are those who can discuss the specifics of multiplayer, or the details when it comes to glitches and graphical prowess. Those who do frame-counts in fighting games, and can argue to death how removing certain RPG elements from various RPG sequels were a good or bad move. And, as much as gamers loathes it, discussing the roles of females or minorities in gaming is part of that.

Feminist and social critiques are part of literature, theater, film, and TV, and if gamers are strong advocates of gaming as art, and I am, then you have to accept that element of criticism as, if not agreeable, than at least valid, as part of the overall aesthetic of gaming. If you aggressively disagree with the criticism, that’s fine. To deny it any sort of legitimacy is a problem, though, and decreases gaming’s role as legit art. To aggressively push tactics that threaten the well-being of such feminist critics, or even to go out of one’s way to name-call, or create games and videos that de-legitimize these feminist critics, is another matter entirely: it’s petty and vindictive, and has no place in any form of pop culture, let alone gaming. There are those who are there claiming such antics are in place to expose feminist critics as self-serving, false victims catering to a gullible audience to make money. The problem here is two-fold. 1) Ignoring the critique to attack the author does little to actually de-legitimize the critique itself (this form of attack is what is called “ad hominem”), and 2) misunderstanding the financial burdens of the (most likely) freelance writer; asking for money in a kickstarter/patreon world is a legal form of revenue, both by the state and the federal government. Gamers who understand the financial struggle in their daily lives seem uncomfortably upset with writers looking through other avenues to earn money, particularly on the backs of criticisms they heavily disagree with. Unfortunately for them, this is a free country, so capitalism told me.

What makes it hard to get behind the current role of gamers is how this attitude is more or less geared towards women. They will tell you to the death that it’s not, but considering that Gamergate began specifically with two incidents involving women, it’s hard for that argument to gain traction. Is there a male-based incident that is also riling up gamers concerned about journalistic integrity? Perhaps, but it hasn’t crossed my way, and I am open to suggestions. I suppose we could point to the JonTron/Tim Schafer incident, but that had been triggered specifically by a Sarkeesian video. What I’m asking is if there is a specific, male-based incident outside of any association with Quinn or Sarkeesian that also brings to light the corruption of games journalism. I’m curious to see it.

Gamergate supporters will often emphasize the fact that those people who have harassed Quinn, Sarkeesian, and prominent game critic Leigh Alexander (the subject of the above picture, where there seems to be a gross misunderstanding of Time’s Terms of Service, and a failure to note that Alexander’s piece is actually in the site’s op-ed section) are in the minority. In fact, with a bit of clever and distinctive use of carefully crafted screengrabs, they will declare any vile outburst against them as forms of harassment; that they are the victims, being stifled in their efforts for gaming journalistic transparency. This is fantastic work; Fox News is probably nodding in approval. As Don Draper said (a character whose entire life is constructed on a giant lie) once said, “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the topic of conversation.” Which they did, quite swimmingly. There’s little concern over whether Quinn or Sarkeesian are actually okay after their harassment; instead, Gamergate supporters are demanding proof of this and the police reports that were filed (interesting enough, no one demanded proof of Brad Wardell’s accusations). Meanwhile, in an scenario where attitudes and sensations are already running high, outbursts where Gamergate supporters are being told to fuck off for being described as said, white, basement-dwelling men (more on this in the next section) is craftily retooled as examples of harassment of the opponents. Never mind the real fact that telling someone to “fuck off” is, legally and ethically, not harassment – simply provoking the opponent via seemingly harmless ways to anger, in order to utilize the angered response as the “real” attack, is political craftsmanship.

However, when there is overwhelming evidence of gamer harassment, like what occurred recently, when someone attacked Sarkeesian with pictures of child pornography, craftsmanship rears its head again. Still, no one asks Sarkeesian if she is okay. There is a demand for proof, followed by demand for the perpetrator’s name so they can bring him to justice, the implicit tone being that if she doesn’t “assist” the supporters, she’s still part of the problem. Never mind the fact that spreading child porn is flat-out illegal and demands police/FBI intervention; note the distinct divide here. The tone, specifically, was less “let’s work together and find this guy” and more “give us the name or is this yet another lie?!” Gamergate is many things, but primarily, it’s about controlling the conversation.

[An aside: how and why did harassment become some sick mark of honor? Instead of bonding together to stand up against harassment of all kinds, it seems that both Gamergate supporters and opponents are keen to prop up and point out their personal run-ins with harassers, as if to give them validity and their foes discredit. Again, aside from the fact that we’re really stretching the definition of harassment (there has to be relatively constant stream of attacks, or a threat against one’s well-being), this is an awful reaction to all of this, and doesn’t help either side.]

Then there’s #notallgamers – which, similar to #notallmen, and which gamers will insist, emphasizes that such examples of overwhelming harassment does not involve or include all gamers. The problem, again, is two-fold: 1) Of course such examples doesn’t refer to all gamers; not only is this known but its pretty much assumed by default (or it should be – again, this will be discussed later). 2) It is up to gamers to assume the role to directly confront harassers and be models of integrity against those harassers, not whine about the nature of being lumped into one terrifying stereotype. Believe me, I know: as a black guy, I completely understand the feeling of being part of a social group constantly misaligned because of a few bad apples. This is brand new to gamers, so they are struggling to handle this. My advice? Don’t play the victim, but be the light that shines on such vitriol and expose them. Don’t worry about the media never covering your more positive aspects. They never will. Just do good, and be positive about it.

Finally, there’s the question of exactly what gamers want with “journalism integrity”. This Vox article sums the entire thing up pretty thoroughly, and I would highly recommend this Medium article, because news journalism and games journalism do not occupy the same space, and there must be a general understanding of this fact before any type of real understanding can occur. Journalism in general is defined by writers building connections to expose real, in-depth truths about a subject; games journalism allows for more leeway in that fact because it is considered “enthusiast press,” not “news press.” Connections to game developers have always been part of the subject matter, even as game outlets indeed start to engage in real, investigative journalism, like Kotaku did at the very beginning of this piece. This is a fact. Ask any and all former and current editors of every gaming magazine/website ever. Add to this the fact that writers are relatively low-paid and are forced to find revenue through other means, including consulting gigs, it’s extremely important that gamers really understand the full nature of what it means to be a writer for an enthusiastic press before any real discussion over “corruption” can begin. (This Paste Magazine article is also a must-read; journalists are not a hive-mind of planners, but individual humans who err and function off subjectivity.)

There’s a lot here that gamers have to work through. Journalists, however, you are not off the hook.

IV. The problem with [game] journalism

I am on record as saying I actually do have a problem with the current thrust of game journalism, and even though there are many issues that gamers need to work through, I do think the core of Gamergate supporters’ concerns has validity. This is actually very reminiscent of the viewers vs. critics fallout behind Girls, in which both groups aggressively dug into the sand and refused to give ground on the criticisms lobbied at the HBO show. Prompted by this random gag pic of the show’s poster, Girls became an unfortunate symbol of nepotism, racism, feminism, and sexism in Hollywood. Viewers insisted the show represented the terrible state of representations in television today, and critics seemed to… dismiss it? That may not be the word, per se, but critics definitely downplayed these legit criticisms, which infuriated viewers. In the end, viewers actually won, with the slow but steady increase of broader, more racially inclusive shows coming around, and critics being a little more receptive of such socially conscious criticisms. Game journalists, I suggest you learn from your TV bedfellows.

This Badass Digest article makes a great example, in which the writer tries to define the typical gamer and how they think, and this doesn’t apply to me and not to gamers any more. The effort is sound, and there’s a “correctness” to it, but with gamers increasingly identifying as women, minority, and LGBT, such broad, generalized statements on what gamers are and how they think are no longer valid. This goes double for the awful, awful “Death of the Gamer” pieces out there, which does little to actually address gamers’ concerns. Gamers railing against “corruption” may be fairly nonsensical, but thought-process in evaluating the transforming audience is a real concern. These are people with concerns that you need to address, and they are tired of the basement-dwelling stereotype.

Game journalism has become less inclusive. I don’t think I’d use the word “corruption,” but there is the sense that game journalists have gotten egregiously caught up in the world of gaming – its glitz and glamor, its access and swag, and yes, even in the discussion of social justice without putting anything truly behind it. It feels surface-level. Reviews seem to toss out vague statements about the poor treatment of women and/or minorities in games without quite understanding why that treatment is so problematic (which is why I appreciate Sarkeesian’s work even if I don’t agree with all of it). Journalists are constantly fickle with their grading systems, the over-enthusiasm of AAA games seem oddly dismissal about such games’ serious short-comings, and the pick-and-choose nature of which indie games are worth looking into wildly random. And yes, perhaps there should be at least some sort of disclosure of which writers, at the individualistic level, are connected with which game companies or services. (Although I don’t think this is as big an issue as Gamergate supporters do, since, as mentioned, most gaming websites have such close connections with gaming companies and services by default.)

But the bigger issue is that wall that game journalists (and, to certain extent, most prominent bloggers and writers in general) have built in front of their fans, which prevents them from seeing the audience and the dialogue around games changing. Sites like Kotaku, IGN, and Destructoid feel increasingly loud and flashy, by design, gearing themselves for the young white (basement-dwelling) male, the very audience that they seem to be actively excluding now (without even bothering to be more inclusive of broader, more diverse audiences). These are sites with few female and minority staff members, sites that have had documented behind-the-scene issues with their staff that seem to go unaddressed.

In addition to some sort of disclosure about writer-to-company connection (which the Vox article does mention is happening), it may be in these sites’ best interest to cool it with the hostility and the “end of the world” declaration on the gaming public (and this Slate article explains why). It may be time for any and all references to that stereotype of “the gamer” as a young, fat, white, basement-dwelling nerdy virgin to be put to rest permanently. It might be time to start a real, close dialogue with the audience, assess games with a more critical eye, explore more investigative pieces, and open up the world of gaming to explore more outlier indie games. And please, for the love of god, stop whining about how hard you have to work while exploring venues like PAX, SDCC, or E3. I don’t think you quite grasp how off-putting that is, particularly in front of an audience that probably will never have a chance to attend.

Journalism can do better. And I will never say that journalists should stop tackling feminist readings of certain games, but we should discuss feminism for a bit first.

V. The problem with modern feminism [and most -isms of today]

The above tweet fails to realize that, technically, that is Anita’s goal, and indeed the goal of most feminist readings. It’s not necessarily the point to “see sexism everywhere,” but to have, at least in the back of your mind, a more critical eye when looking at or experiencing media, to question how and why certain roles that women partake in are they way they are. The point of all cultural reviews is to prompt readers to cast a critical eye on the systematic use of coded tropes within the books we read, the movies/TV shows we watch, and the games we play; this is how art, and our culture, advances. There is a line, though.

“SJW,” or “Social Justice Warrior” is a tossed-around term that is usually used to rail against those who are deemed to be for censorship or political correctness via their one-track minded cause. “Social Justice” – and let us be very clear about this – is a good, good thing. SJWs, however, usually refer to the people who uses the cause to aggressively attack the status quo in uncomfortably ways, often missing (and flat-out refusing) any sense of context or inclusiveness. SJWs want a “thing,” and fail to understand how those “things” bring together or connect to other “things.” To SJWs, it’s do-or-die in a real-world war that is constantly trying to destroy the very cause the SJW is rallying for.

I am a feminist. I do worry that feminism is growing… exclusive, though. There have been examples of its dismissiveness of black women and LGBT issues, and there has been coded language tossed about that has implying the dangerousness of black males. Certain well-known feminist sites rally against people like Seth Macfarlane and Daniel Tosh, but then write what could be categorized as an “ironic” take on R. Kelly. Modern feminism also tends to downplay and even joke about subjects like prison rape, homosexual women, and transgendered females. I think its more aggressive advocates do approach SJW levels, absolutely dismissing any and all male assistance, and perhaps get too caught up in the idea of “speaking for all women”. Understand that I believe this only a small percentage of modern feminists, but I think that in the need to feel part of the collective, feminists won’t speak against one (or a few) of their own.

As a feminist, it’s my duty to speak up if and when feminism ignore real, black and/or LGBT feminist voices. (In fact, I did, when I wrote this long tirade against intersectionality). Feminism is a cause that I believe in, and I love that it has been gaining more traction and attention, but I’m very concerned that it is leaving its minority, LGBT, and its male supporters behind. It wouldn’t take much to tackle feminist’s intersectionality problem – more inclusive writers and more observations and analysis of black and minority females in various roles in media, whether in films, TV, or games, would help to open up the issue and give feminism a firmer footing to stand on.

—————————————————-

Given all these issues presented, even though I have my issues with game journalism, I think I tend to be on their side over the Gamergate supporters. I find their approach uncomfortable, engaging in a level of, if not hostility, then forwardness that seems more demanding than revolutionary. Like the Medium and Vox articles imply, it is not clear what exactly Gamergate supporters are aiming for (and I mean a very, very specific demand, as opposed to the nebulous “more accountability in game journalism” mission – how do you do that?). Being that every incident they’re railing against involves a woman’s involvement in games adds to the discomfort; perhaps if there was a male-only journalistic situation that raised eyebrows would I be more receptive to their cause. As it stands, though, it seems that while gamers, game journalists, and feminists have their issues to work through, it is gamers and the supporters of Gamergate that, at the very least, need a very specific goal, something that goes beyond the drive to remove Quinn, Sarkeesian, and Alexander from the field (since they managed to do this to so many other writers), and that goes beyond removing feminist critiques from game journalism, because I REFUSE that notion one hundred percent. I will not be swayed on this.

In either case, there’s a lot to be discussed here, and I’m ready to talk. Is everyone else ready to do the same?

Comments are closed