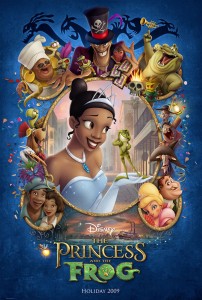

When John Lasseter announced the return to traditional, hand-drawn animation for the new Disney film The Princess and the Frog, people got excited. After the negative fallout from 2004’s Home on the Range, pen-and-paper animation for the cinema was a dead prospect, save the maybe-occasional independent/foreign/low-budget anomalies (Persepolis, The Secret of Kells, Winnie-the-Pooh). But here we were: Disney was ready to back a new, fully-fleshed, big-budget animated movie again. And while some people bemoaned yet another princess-based tale, the idea that this could lead to new, fresh, original 2D animated films was way too tempting. All it had to be was a hit.

And it was… kinda. The Princess and the Frog opened to positive reviews, but with a budget of $105 million, it barely made back its budget domestically. It did much better worldwide, grossing over $265 million, so it wasn’t a colossal failure. But still, the passion and excitement behind the return of 2D animation was palpable. Even the producers and executives were excited by the life of the medium and seemed eager to pursue in different ways.

And then… it completely stopped. Like a 80 mile-per-hour train colliding into a diamond wall, the passionate voices heralding the hand-drawn format suddenly died out. Even critics and average proponents of 2D animation went silent, save for a few folks here and there. It all became a dream deferred, and especially so when Bob Igor announced that there were indeed no plans in the works for traditional 2D animated films, going so far as to layoff a majority of their 2D animation staff. The medium that seemed to be right on the verge of a resurgence dried up like an open bottle of ink.

Why? Perhaps part of the problem is that The Princess and the Frog didn’t do as well as Disney may have hoped, but tons of 3D CGI films do poorly, and they’re still going strong. Hell, in the last couple of years, stop-motion has exploded with the occasional work – Coraline, Frankenweenie, ParaNorman, Pirates! — and none of them were exactly runaway hits. So why did 2D animation get the short stick?

To try and answer this question, I re-watched The Princess and the Frog, to see if the answer was somewhere in the frame. To be honest, I had saw the film in theaters with a friend, and we both came away from it with a very blase attitude. We both kinda liked it, but deep down inside we were rather unimpressed and, frankly, disappointed, which seemed counter to the opinions of most of the critical community. But we couldn’t express why we were so disappointed. And now, since I have a stronger critical mindset (thanks to blogging and reading other blogs), I want to give the film another go, and see why, perhaps, the IDEA of The Princess and the Frog was more popular than the actual movie. In other words – is the very film that signaled the return of hand-drawn animation the very thing that killed it?

The Princess and the Frog, upon the fantastic revelation that it was going to be 2D, hand-drawn animation, had a choice: should it be a straight-forward, character driven, clean n’ direct princess tale? Or should it be a sillier, wackier story of the Looney Tunes mold? The cast and crew, as talented as they are, hadn’t made a 2D film in years, and the last batch that came from the studio were barely mediocre at best, so the decision to make it a mixture of both was probably not the best one. Audiences may have been drawn into the story but it didn’t keep them there – the disappointing and sad truth is that most people seem uncomfortable with their serious animation mixed with their wacky animation.

Do not get me wrong. The Princess and the Frog is an amazingly beautiful movie. It captures the power and glory that hand-drawn animation can do, and it is a delightful experience, even upon my re-watch. In fact, I think it actually gets better at some points; but its flaws also become more and more apparent. And I don’t mean it in a nit-picky way (although it probably comes off like that), but in terms of the financially lukewarm reaction and the sudden drop-off of 2D-animation championing, I just wanted to figure out why this film didn’t “have legs” for the medium like so many people felt it did.

Of course, there’s the easy excuse – it stars an African-American cast within an African-American setting, and because of which, mainstream white audiences didn’t go see it. I don’t think that’s true. Or, rather, not quite as explicitly direct as that. Most studios, Disney in particular, craft their stories of black people in such a specific paradigm, focusing heavily on ideas of strength, overcoming, power, sass, and self-efficiency, which makes it difficult to get into the most important part of creating character and conflict – vulnerability. Part of this is because executives seem extremely afraid of offending black audiences, they mistake vulnerability for weakness, fearing either might rally the NAACP to attack their lead as a shallow showcase of black women. So Tiana, our “princess” in play, is perfectly fine on her own.

This creates a problem; Tiana, in truth, has no stakes in the story. After all, she just wanted a restaurant. Hell, she managed to buy the place that she always wanted within the first 15 minutes of the film. The conflict and thrust of the film is really over Dr. Facilier (the Shadow Man) and his desire for Prince Naveen’s money. All these things – the Shadow Man’s deal with Naveen, Lawrence’s envy of Naveen, Naveen’s own lack of funds – have shit-all to do with Tiana. Thinking about it, she gets involved with all this in a silly, convoluted fashion – a higher bidder threatens to steal Tiana’s purchase right under her nose, she gazes at the stars depressingly, then in some bit of desperation, kisses the transformed-frog Naveen, which turns her into a frog herself, which is then followed by some wacky antics which flings them towards the bayou. One could probably argue that the entire scene is a play on the typical “wish upon a star” trope, a subversion of the various princess films before it. But because Tiana isn’t exactly part of the actual conflict, this subversion is pointless, since it really doesn’t have anything to do with the plot. Tiana is dragged along because the script demanded it – and for some reason, on this trip, she learns that she needs to love?

One could argue that The Princess and the Frog suggests, uncomfortably so, that Tiana, a woman who had agency and her admittedly justified and perfectly-fine dream to own a five-star restaurant, ought to drop her dream and get with a guy (Mama Odie’s insistence that this is so is particularly telling). The film goes through great length to combine the goals of success and love into one perfect Platinum achievement, but like any gaming achievement, they’re really unnecessary, and this overwrought metaphor gets to one of the many core issues with the film – Tiana really has no agency here. She’s roped up into a situation not by her own choice, but by circumstance. The main villain, who is a cypher all his own, has no personal stake with her. His concern is the prince – and even that isn’t personal. It’s a long con for his wealth (or what’s left of it), and Naveen is so ridiculous that he’s really just the comic relief with a point. Is this Tiana’s story or Naveen’s? The film doesn’t say.

The various audio commentaries on the Blu-ray dances around a lot of these problems as strengths, despite a lot of background talk of the script going through many, many revisions. Also, not a single woman was involved in this creation of the story, let alone a black woman. This isn’t necessarily the root of the problem, but in relation to the difficultly of giving Tiana stakes or agency, I can’t help but mention that it has to be part of it. Getting a black woman’s say on the direction of Tiana’s tale couldn’t necessarily hurt things, could it? The audio commentary is particularly telling: in their desire to do a “princess movie for people who don’t like princess movies,” they only end up paying lip service to one. There’s a “princess,” and there’s a “frog,” but that’s really all there is, and breaking down the princess fairytale doesn’t necessarily bring anything else to the table – and making the characters black doesn’t hide this.

The three secondary characters that Naveen and Tiana meet along their trip back to the city feel just as untethered to the story as Tiana is, and the set up to the meat of this section is weirdly rushed. Upon getting ported out of the city towards the bayou, there’s a “blink and you’ll miss it” moment where Tiana hears a dog speaking English, which sets up the ability for the humans-turned-frogs to communicate with Louie, the alligator who wants to play in a jazz band, and Ray, a lighting bug who is in love with a star, along with Mama Odie and her omnipotence to see and hear everything. This is tonally confusing. According to the audio commentary, Louie originally was supposed to be another human who was transformed by Dr. Facilier. Presumably dropped because it was too complicated (it isn’t) or it takes too much away from the story of Tiana and Naveen (it doesn’t), it raises the question of a more thematic nature – namely, that there is none. It’s funny and enjoyable to see the extreme hilarity of gator who wants to sing, but lacks the resonance of, say, a rat that wants to cook. Louie’s drive is perfunctory and defined by its comic relief since there’s nothing behind his desire. It probably would have worked better if he just was willing to help them, in contrast to the vicious gators introduced five minutes beforehand.

Ray takes the “helping” mantle, which gives him a tighter connection to Naveen and Tiana, and his outlandish idea of love – he has his hearts set on a bright star named Evangeline – contrasts Naveen and Tiana a lot more closely, especially since both she and he have separate conversations with the insect that are regulated to their respective approaches to love. Ray is the strongest secondary character, although he is a bit overbearing at times, but because he still is more of a helping figure than someone tied to the characters, his death, while effective, lacks the emotional one-two punch that it should have. In some ways, I’m reminded of the death scene of Robin William’s robot sidekick in Flubber (not a film I exactly recommend). It’s effective and it’s meaningful, but not exactly earned.

Then there’s Mama Odie, who arrives, sings, exposits, then never returns. Mama Odie is a problem in so much that she just pops up in godmother fashion and, in the form of a musical, tells Naveen and Tiana – and by proxy, the audience – what they need to know. In fact, her song, “Dig a Little Deeper,” is so specific and direct that its jazz-infused choir awesomeness is overshadowed by its on-point message: “HEY! THIS IS WHAT YOU NEED TO FEEL.” (In fact, a lot of The Princess and the Frog’s songs, while musically fun, more or less simply reiterate the plot and feelings of the characters in the current scene, to their detriment). I love Mulan’s “Be a Man,” but that middle part kills the song dead. Again, like Louie and Ray, she isn’t connected to Naveen or Tiana, which makes it feels like everyone is striking on their own.

That’s The Princess and the Frog in a nutshell. The film is a constant push-and-pull of juxtapositions, leaving nothing that connects or sticks with you. Is this about Naveen or Tiana? Is this a princess tale or a subversion of it? Is this a cartoony tale or a serious one? Naveen is crushed by a book and jumps back to life; Ray is stepped on and dies. Aside from the jarring difference here, this results in a movie trying to be both comically ironic and deeply sincere, not only in its story but in its animation as well. Again, the visuals here are fantastic, but at times overwhelmingly so; only in a few bright spots do we get to see the animation being effective to watch, letting characters be characters instead of part of an excited, vibrant tapestry. I often think of it as the film trying too hard, a desperate plea of “Look at the hand-drawn animation! Isn’t it awesome!?” The sad part that it is awesome, but in the way where spectacle trumps practicality. More is less, and it’s a lesson that I feel may have been lost here.

So, as much as I’ve grown to enjoy what The Princess and the Frog has to offer, I can’t help but point out that its deficiencies may have been more detrimental to its success than the creatives might have believed. I can’t say for sure that this film killed off the burning desire for hand-drawn films, but in all honesty I can’t say it helped. It functioned perfectly fine, flaws and all, but audiences reacted to it with a shrug, a sentiment that clearly went up the chain of command at Disney HQ. There is a scene in The Princess and the Frog where Tiana, Naveen, Louie, and Ray do battle with a couple of frog hunters. It, like the rest of the movie, works very well but truly has no purpose. Films require that every scene and every character should matter. The Princess and the Frog comes to the correct answers in its visual panache, but it, sadly, forgot to check its work.

Comments are closed