The casting of Ben Affleck as Batman in the soon-to-be-teased-relentlessly Batman/Superman film caused quite the stir among the internet, filled with spiteful Twitter comments, rage-filled Facebook posts, and lists-among-lists of why he’d be both great and terrible. Of course, this kind of massive knee-jerk response is nothing new, since there was a tremendous amount of it when Heath Leather was cast as The Joker, or when Michael Bay announced his take on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Riling up the fanbase has become in itself a new form of marketing, whether in positive forms (which is the key to Comic-Con’s specifically-designed trailers and teasers and… amusement rides), or negatively, which one could say is what propelled a giant portion of controversy over Man of Steel and World War Z. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and to studios, all they really care about is that sweet, sweet green.

I wanted to take a step back, though, and look at where we are now. Watching this geek-based reaction from a distance, it’s rather crazy if you think about it. This kind of response would have been completely unheard of back in the 90s – hell, even in early 2000s, this egregious “stirring of the pot” would have been nigh impossible to do. Tracking this kind of response backward yields some interesting results – through Batman Begins, Iron Man, the entire Marvel film universe, Scott Pilgrim, Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull, Harry Potter and Twilight, just to name a few. Sure, the emphasis of “the franchise” has become the raison d’etat of Hollywood nowadays, especially since overseas is now where the real money is (resulting in sequels to films that hardly deserved them – there’s a third Chronicles of Riddick, despite the second one completely bombing). The question is, where did this out-of-control bloated behemoth stem from? Oddly enough, it all began with one film that indeed tried to spread across all these entertainment platforms, and failed. In its ashes was born this blockbuster monster of cinematic proportion that is now creeping into television, video games, comic books, and animation. Enter The Matrix.

——————–

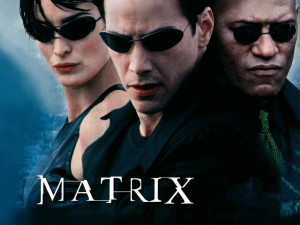

It seems so far ago, but when The Matrix was released way back in 1999, it was essentially The Pirates of the Caribbean of its time: a pleasant surprise that no one was expecting. Sci-fi films were still relatively niche and most of them that were released in the late 90s were terrible, just like any other pirate film that entered the cinematic landscape. But here was The Matrix, its tinted green cinematography overlaying audaciously new (at least in America), gravity-defying fight choreography, all couched in the basic question of what is reality, which seemed particularly relevant in the rise of what the internet and virtual reality were soon to become. The Matrix was an eye-opener, and while I personally was somewhat lukewarm to it when I first saw it (I warmed up to it more on subsequent viewings, but I’m still not what you would call a fan), I can’t help but acknowledge the power it held, especially within the geek community, which at the time still was a forgettable market to Hollywood. Fansites exploded across the internet, and people, for a long, long time, cosplayed in their black trenchcoats and sunglasses as they went to see the film over and over.

No one knew it at the time, but this was the beginning.

The Matrix nabbed over $450 million by the time the film ended its theatrical run. That cashflow began all the talk and speculations of a sequel, which is normal for any winning film, but the Wachowski’s want to do something insane – make TWO sequels. The “trilogy” concept more or less died out with Indiana Jones, and the only thing that was considered worthy of it was the Star Wars prequels, and we all know how well that turned out. The same sentiment, of course, could be said of Reloaded and Revolutions, and both franchises showcased how the money-making bloat of the summer film franchise could overcome both critical AND public conception. But unlike Star Wars, which was always (and will always be) an unstoppable franchise force, The Matrix was new, and while the first film was proven hit, the question of whether it was franchise worthy was something else entirely.

The Wachowskis, of course, sold us all a bill of goods. And it’s not as if The Matrix didn’t have enough content to sustain a number of new, interesting, and intriguing stories within its premise. With all their claims of possessing numerous stories to tell, it’s extremely surprising that Reloaded and Revolutions were what we got. In addition to all that, though, were ideas that slipped its way into different media – anime (The Animatrix), video games (Enter The Matrix, The Matrix Online, and The Matrix: The Path of Neo), and comics (The Matrix Comics). The Matrix franchise was trying its damnedest to worm its way into the pop culture conscious just like Star Wars did so many years ago. But there was a glaring problem: the sequels kinda sucked, about half of The Animatrix animes were in any way decent, the games were broken and not very good, and comic culture wasn’t prevalent enough to warrant enough a large readership for the comics themselves.

The problems with Reloaded and Revolutions were twofold, narratively and thematically – they took focus away from the cool (and much more interesting) parts, the Matrix itself, and focused on Zion, the “real world,” which the writers failed to mine for anything worthwhile. Secondly, they turned the philosophical questions of reality and instead asked religious ones, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing per se, but again, the Wachowski brothers weren’t half-assed to be nuanced, and when they were, it was nonsensical. The games, the comics, and anime were supposed to answer all the lingering questions – but 1) the internet had yet to become so interconnected to the various media forms, so many people barely bothered with that, 2) the films themselves were so problematic that few people actually cared, and 3) those that did were only left with MORE questions. (In some ways, this is what doomed Tron: Legacy – there’s little interest in exploring a franchise if the original source isn’t all that good in the first place.)

But let’s be clear here: the failure of the games and mediocre reactions to The Animatrix would have signaled that this crossing-of-the-media-streams was fatal. Sure, it made money – a lot of money – but it was so complicated and convoluted that by the end of it all, Hollywood rightly thought it wasn’t worth it. It was most likely Harry Potter or Lord of The Rings, the successful book series turned film in 2001 that really turned all that around. Looking at the remnants of The Matrix, everyone learned some valuable lessons – primarily to work with franchises that were already established and easier to comprehend. Coupled with the rise of Comic-Con and geek culture (along with social media), Hollywood specifically realized that utilizing these established fanbases and liberally sprinkling them with controversial BS would be all that was needed to make this bloated, endless machine of summer franchises, arguably made purposely controversial to increase buzz. There’s no way that the Ninja Turtles film will be any good, but every site seems rabidly fascinated with each and every casting call.

From the ashes of The Matrix franchise, came forth the endless stream of loud, riotous, special-effect heavy franchises that rip through theaters and tear-ass across theaters, TV, comics, and video games. Hollywood learned lessons from those burning embers, lessons that now have been taken too far in the wrong direction. Perhaps we need a similar crash-and-burn these days, but I doubt it will be enough to stave off the bloated behemoths coming to theaters in the years to come, and certainly won’t end studio executives mining the dregs of our entertainment past to find the next new endless franchise – I’m pretty sure there will be a Matrix reboot or TV show in the next five years. Yet for a moment, The Matrix was a thing, and we experienced all of it, unwittingly opening a door that we may never close.

Comments are closed