Back in the early 2000s, game designer Warren Spector announced he was working on Epic Mickey, a new game from his brand new video game company, Junction Point Studios. Spector’s early remarks about this new venture included a lot of commentary about returning Mickey to his more mischievous roots, a comment that, not surprisingly, got taken out of hand by the most of the public. The term “mischievous” was, for some reason, interpreted as “dark and adult,” and it didn’t help that a lot of the early press about Mickey “controlling life and death” seemed to imply that Mickey was to be some Grim Reaper arbiter of mortality. Spector never quite denied the thrust of this out-of-control hype; an early idea included Mickey sporting an “angry” look when you made “bad” choices. Oh, that’s right – Epic Mickey included a morality system, a game design that, outside Mass Effect, Dragon Age, or Fallout, shouldn’t exist in any game ever.

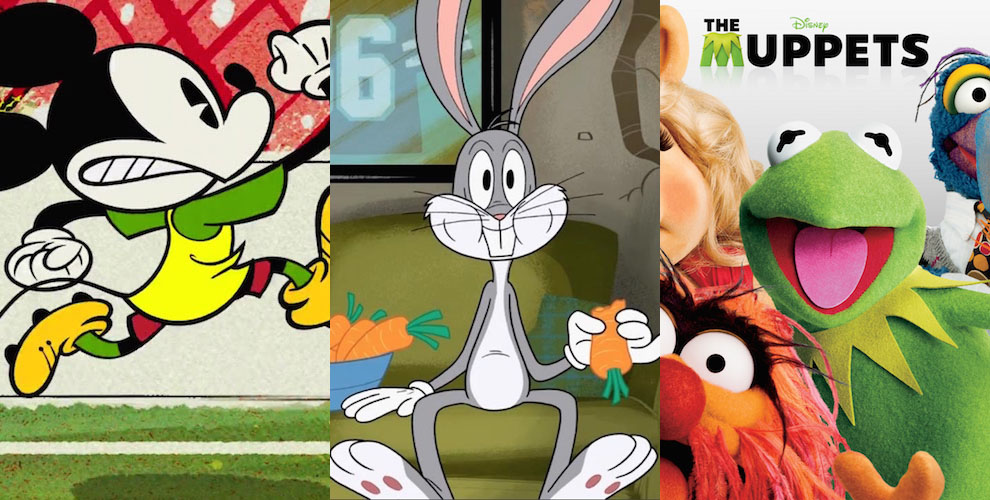

And certainly Epic Mickey. While the first game did okay financially (while not being as dark or adult as the hype made it out to be), the second game did so poorly that Disney cancelled all future iterations of the game and closed down Spector’s studio. Part of that, of course, is due to the gameplay and camera issues being problematic and unfixed, but beyond that, there’s something blatantly disingenuous about that hype – the idea of Mickey Mouse, of all people, being some kind of tortured, complex anti-hero. What’s worse is the fact that so many people believe that this was part of Mickey’s identity before Disney “sanitized it,” an idea that completely misinterprets both Mickey Mouse and the company that birthed him; clearly, no one actually bothered to re-watch the old Mickey shorts. How the idea of mischievousness became some kind of hardcore miscreant is a perfect example of writers and creators struggling with bringing classic characters to modern audiences – your Supermans, your Bugs Bunnies, and, currently, your Muppets. It’s not the personalities, and the so-called dated ideals those personalities represent (an idea that’s overly-cited as to why these characters struggle to capture today’s audiences). The problem is one hundred percent in the execution, in the writers’ and creators’ unambitious, restrained settings and premises that prevent these characters from thriving.

——–

The strangest thing I’ve read in the last year was when Erik Kuska, a producer on Cartoon Network’s new Bugs Bunny cartoon, Wabbit, wanted to avoid cliches like the anvil gag, preferring to utilize “modern heavy objects to cause pain.” I’m not even sure where to begin to respond to this. Should I start with the fact that anvils were dated even back in the 40s/50s, when they were first used as animated comic props? Should I emphasize their datedness even back then was part of the entire joke? Should I point out “modern objects” were always used to cause pain regardless? (Safes, cars, tanks, TVs, computers, and ships all have been used to flatten/hurt cartoon characters.) Or, perhaps most confusingly, should I mention that Wabbit doesn’t exactly use that many “modern heavy objects” in the first place?

Bugs Bunny has been going through a struggle himself. For all the problems in Space Jam – and there are a lot – that probably was the most accurate take on a modern Bugs in years. Bugs is passable in Back in Action but is drown out by the rest of the animated figures and an overly-frantic human cast. He spends too much time trying to figure out other people in The Looney Tunes Show, a cartoon that loved circuitous dialogue for some reason, the kind of dialogue where people would talk at each other and poke holes in the very exchange that was happening (whenever it broke from that, it was occasionally watchable). And in Wabbit, Bugs spends a bit too much time being confused, even, strangely enough, when he’s confidently in control of the situation.

The thing is, personality ticks aside, these modern takes on Bugs aren’t inherently a problem. Bugs’ original incarnation was a wacky loon, an instigator of chaos before being toned town into a more snarky, self-aware jerk whose power is defined by unleashing his comedic wrath at anyone who slights him. His more recognizable personality is a take on the Marx Brothers (with a smidgen of Clark Gable), so it makes sense to evolve it in a new perspective, particularly for an audience that isn’t familiar with 1950s Hollywood. (Yet, personally, I do question Bugs’ laid back, semi-pushover personality in The Looney Tunes Show, if only because he’s defined not by a specific personality but a complete lack of one.) But the bigger issue isn’t him; it’s the kind of stories he (and the rest of the cast) are involved in, which were no more then slightly elevated sitcom cliches. Pets that acted differently in front of various people. Annoying neighbors. Trouble with women and dating. The DMV being shitty. Only when the episode allowed its inherent cartoonness to do its thing did the show finally exhibit some life, something to stand out beyond its sitcoms cliches (which is odd, since The Simpsons, Family Guy, and American Dad managed to do what The Looney Tunes Show never bothered to embrace, and they came before that show).

That’s what makes it all the more baffling. The Looney Tunes characters were not only defined by their own personalities, but by their personalities as inserted within an insane, absurd, wacky plot, which The Looney Tunes Show lacked. Wabbit, god bless its soul, attempted to be more ambitious, but still seem to struggle with making its scenarios truly loony. It’s at this point I could get into a whole thing about basic animation principles, including exaggerations, anticipations, and squash-and-stretch techniques, but the gist of it is that Wabbit fails to really employ any of those techniques to full effect (a result of an overall industry adverseness to those kinda of visual tricks). But those tricks are paramount to what makes the Looney Tunes characters and scenarios work, and denying them will only lead to a bland, unambitious show – a show where its characters, no matter how you adjust them, can’t actually do anything to make them stand out.

It’s a lesson that ABC is learning with the sudden drop in ratings with their recent take on The Muppets, a drop so significant that one of the showrunners left the show in anticipation of a new-new reboot. There’s a lot of issues with the show, and there’s plenty of pieces out there attempting to point to the core problem: was Kermit/Piggy too mean? were the other characters wildly underused? was it too sitcom-y? did it need to be more variety-based, even though variety shows are no longer viable forms of entertainment? Part of that, again, has to do with how we (mis)interpret the original show. There’s a lot of arguments out there, for example, that Kermit was always mean, but there’s very distinct difference between “variety show” mean and “sitcom” mean. (There’s a very lengthy argument to be made about how “meanness” on TV has become this weird, confusing sticking point among audiences, but I digress).

But, again, personality changes to the Muppets isn’t the core problem. Pepe, Gonzo, and Rizzo had some minor tweaks, and they came out quite good. In fact, I’d argue that by the final three episodes, the show itself made just enough adjustments to right the ship: the weirdly controlling Kermit became a softer, more endearing frog, and the show overall had hit the right notes between its sitcom trappings and its more loony aesthetics, with more absurd situations and antics in the mix. Still, I feel as if it’s still a bit too sitcom-y, as forced through ABC’s primetime slot. Here, I would suggest they might take a cue from Mongrels, and open up the characters and their experiences outside of the central locale of the Miss Piggy show. Something that could allow the puppetry and the rich cast comprised of that puppetry to shine. The variety show may be dead, but the musical show is making a comeback, and it might help the show to push more puppet routines into the sitcom narratives, to really let the Muppets thrive. It’s not just the Muppet characters that people liked, it was the whole, whiz-bang showmanship of Jim Henson’s creations in action.

We can end this here by comparing the Epic Mickey failure to the success of the new batch of Mickey shorts. In fact, it might be good to look at the three rounds of these shows – the originals, the shorts culled from Mickey Mouse Works/House of Mouse, and the current batch that’s winning Youtube. (We could also examine the various ways in which Disney remixed, re-issued, and re-purposed its shorts for various generations). Each iteration worked very well, not only by placing Mickey (and the gang) into situations that connected to the current audience, but also by never losing sight of the gang as who they truly are (also, adjusting the look and designs to match current visual standards helped). It’s all of that, really: Mickey has always been loose and broad enough to fit within any template, but the truth is, so have the Muppets and the Looney Tunes characters. It’s just that certain templates have restraints that don’t always work in the characters’ best interests, like sitcoms or morality-based games. If current creators look past those restraints, they’d be able to combine what made these characters shine in the past, re-contextualize them in new situations for the present, and allow them to succeed in the future. I assure you that anvils are not the problem.

Comments are closed